It will come as no great shock to you when we tell you that apps change over time. New design, different technical functionality, different market demands — these forces conspire to change what apps are and how they work. Let’s find out how you can avoid becoming one of the complicated apps!

For example, Instagram probably wasn’t planning on having Instagram Stories until Snapchat surged into the world. Over time, new feature development and app upgrades are important. However, we’ve noticed something. As apps get older, they tend to drift in their focus. They add so much functionality that they’re difficult for new users. Super-users love them — but new users can’t figure them out.

So what’s going on here? What makes apps swell to such overwhelming complexity that they become unusable?

We’re going to find out. Here we go!

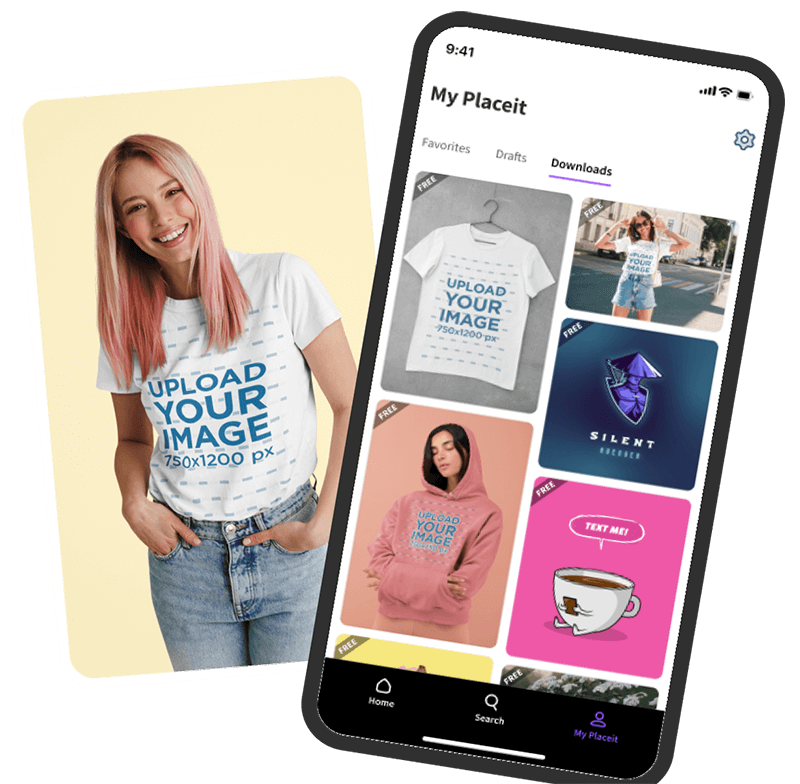

🔥 Check out Placeit’s app!

But first, an example: Evernote

To get us all on the same page, let’s start with an example that effectively demonstrates this problem: Evernote.

For those you who haven’t heard of it, it’s a note-taking and organization app that quickly and easily lets you take notes as you browse the web and store them in an organized, searchable way.

Let’s take a quick look at their web-based app to see how a new user (me) might start using it.

They have Google sign on, so it’s easy to get started. Once you’re in, they get you to select what sort of thing you want to do with the app — organize your life, be more productive, or take better notes — and then you’re into it and going (I picked be more productive).

Then, you get to a four-step process to learn the basics.

To be honest, I’m not that into it at this point. I mean, this is supposed to make me more productive, and I get that there’s bound to be some onboarding experience. But at the same time, 4 steps seems like a lot for what is supposed to be a simple note-taking app.

Anyways, we’ll keep going. Step 1 is trying out a new note. This is pretty basic and works like you expect. I actually liked this step — it’s close to how I would use the app.

Step 2 is just a popup window about notifications that, to be perfectly honest, I didn’t read this. I just clicked away so I could get it crossed off my list.

Step 3 isn’t a step at all, but rather a link that goes to another Evernote product called Web Clipper.

At this point, I’m not in the frame of mind to get another Evernote product because I’m still working on the first one. Especially because this second product looks like it’s going to have a whole other onboarding process, AND it doesn’t know who I am, AND it seems to have its own links around discovery and exploration. When all I wanted was to take notes.

Anyways, not doing that, so we press on to step 4.

Step 4 is, again, just a popup that, once again, is telling me to download more Evernote products. This time, it’s going to sync my phone and stuff.

Again, this is a valuable feature to have. But again, it doesn’t help me get started.

Because now I have the problem that I’m theoretically “onboarded”, but as a new user I still don’t know what any of this sidebar stuff does. I can assume that some of it will “create a note”, and others I can infer pretty easily, e.g. the one that looks like a calendar probably adds dates or links to my Google calendar or something.

But there’s also big swaths of the basic product I don’t know how to use.

For example, for me, checklists are a key part of productivity.

But during the onboarding, there was no mention of checklists. Turns out, you create them in the note function, but this wasn’t highlighted.

Finally (since I’m a thorough researcher), I poked around Evernote some more to see what they’re actually offering.

And what I found surprised me after what was a pretty rubbish onboarding experience.

The product has a lot of great stuff. Users can tag their notes super easily for fast and efficient note organization, you can organize notes into notebooks, you can star notes or notebooks to create shortcuts, and it has a great search. Plus, it’s easy to share your notes, either to a social network or with a link, which is great if you’re trying to coordinate with someone else.

What’s more, just being in the product showcased some superb design, which definitely made me like it more.

But other things, like the Web Clipper, were completely lost on me.

And this is the crux of the problem: products reach a point where they’re so tailored to advanced users that newbies struggle to know what to do.

And to be clear, this isn’t just a Evernote problem. Lots of apps have this issue. For example, consider the case of Airbnb.

Another Example: Airbnb

Airbnb was originally a simple accommodation website. People list their own places and other people come and stay at them. Here’s a screenshot of their homepage from 2009:

As you can see, it’s pretty straight-forward: you enter your search parameters and hit ‘search.’

Now, compare that to a screenshot of Airbnb from today:

As you can see, their core offering is still there (in the red box). However, far more screen space is being dedicated to experiences and restaurants:

The site doesn’t feel like a website where you go to book some cheap accommodation. Rather, it feels like a place where you go to look for ideas for your trip. It’s like a guidebook crossed with TripAdvisor.

Even the search bar is no longer asking ‘where are you going?‘ but the far more exploratory ‘Try Cape Town.’

Of course, if you’re like me and you’ve used Airbnb before, this is nothing more then a mild annoyance at most, and some great functionality at best. Now, you can book your totally unique accommodation AND learn all about where you’re going without leaving the site (or app)!

But what if you’re new? What if you’ve never used Airbnb? Is it clear what value they offer? Is it clear what you can get from their service? I’d argue that no, it’s not especially clear. In adding more features like restaurants and experiences, it makes it more difficult for new users.

Why products drift

So why does this product drift happen? Why do products become progressively more difficult to use over time?

The answer is part business, part UX, and part product. We’ll tackle it bit by bit.

The business

The first part is the business.

Product managers, marketers, and app builders are always looking for new revenue streams for their apps. Evernote, for example, is a freemium app, meaning that it’s free to install and use, but you can also pay a monthly subscription fee if you want more features. In fact, they urge you to upgrade on every single screen of the app.

The upgraded features are what you expect:

- Increased functionality

- Increased focus on business users

- More/better customer support

- More storage.

And while a lot of those are valuable, apps following this model needs to offer enough of an upgrade and enough new features that users:

- Think the upgrade is worthwhile

- Will continue to see its value (and continue to pay) over the long term (ARR).

For many software products, this continuing value is about adding features. And that drives feature creep. App builders design features that some users will love so they can eventually charge for them down the line. Alternatively, like with Airbnb, the goal isn’t to charge for them but rather deepen their engagement with audiences. By building out more content and leveraging their review infrastructure to create recommendations, they make it more likely that people will book more aspects of their trip through the app. Thus, driving more revenue.

Another major business driver of this problem is what I call the ‘make everyone happy’ problem.

Apps, particularly those with a broad value proposition like Evernote (but it can happen to anyone), want to appeal to as many users a possible.

By expanding their potential market, they can drive more user acquisition. However, if their effort to create features for everyone, they often end up cluttering the user experience for all but experienced users who know how to navigate the app.

Finally, over the past 3-4 years, we’ve seen apps begin to merge back into single super-apps.

Facebook Messenger, for example, is beginning to add more and more functionality. Renewed business focus on maximizing the collection of user data means that Messenger can now:

- Send images, videos, and organize group chats

- Make plans and keep calendar invites

- Send, receive, and store maps

- Record voice messages

- Send money

- Be a messenger bot for business

- Power live chat for businesses

- Act as micro-stores for e-commerce.

All for an app that is fundamentally the same thing as AOL instant messenger. The result of all this is a renewed pressure for organizations to deliver ever-more functionality.

So those are the business drivers that facilitate feature development. But UX designers and product teams also have a role to play.

UX and Product

For the UX and product teams, the story goes like this.

When apps first start, they focus on doing just one thing. That’s usually what makes an app take off, and this laser focus is a big part of what makes a startup a success. That simplicity attracts the original core of users — people who are looking for a solution that solves their problem, really really well.

Over time, the app gets more popular. Teams grow, timelines stretch, and product teams start to build out auxiliary features and functionality. This might be integrating with someone like Zapier or just offering a new feature, like single sign on (SSO).

At first, these features are great. Users are excited to see the product develop, and it’s not so complicated as to alienate people who are still using it for the first time.

Plus, apps don’t have to spend so quite so much time explaining what the app does (hence the change in copy on the Airbnb site).

And then the trouble starts.

As the product expands, those original users become more advanced. They learn the product more and are more likely to provide feedback on what’s working and what isn’t. They start to think ‘gee, it’d be nice if this product did x thing for me.’

This vocal minority skews the feedback that product owners and developers are getting.

Combined with the fact that many apps experience plateauing growth as the low hanging fruit is consumed, this feedback leads to the natural conclusion ‘we need to make our product better with new features to continue to grow’. Thus, complexity increases.

Apps end up becoming better and better for a small subset of existing users, which has the implicit effect of making the product more difficult to adopt and more difficult to use early on in the user lifecycle.

New users feel isolated and unsupported and are far more likely to quit because the app no longer solves one thing well. Now, it solves dozens of things well… but only if you know how. And that’s why you get apps like Evernote and Airbnb.

The outcome

Possessing a core cadre of diehard fans isn’t exactly a bad thing. These are profitable customers who will sing your praises and love your app. They also give you a jumping off point for spin-off product development. For example, Airbnb now offers Airbnb for business that has it’s own landing page and value propositions:

However, it doesn’t do you a lot of good for new customer acquisition. And the market will respond.

The fundamental problem is that the original need doesn’t disappear. By excluding new users, apps create space in the market for new entrants who are better poised to do the one thing users want.

For example, MS Word is an extremely powerful program — so much so that actually typing a word document can be a pretty unpleasant experience.

That’s why a quick Google search for ‘distraction free writing software’ generated over 800,000 results.

By catering to more advanced audiences, Microsoft alienated people who just want to write a blog post or bang out an article.

It comes back to the fallacy of zero opportunity cost. As product owners consider new features, there tends to be an assumption that more is better, and that by adding features they’re going to capture new users while still pleasing old ones.

The truth is, there is always an opportunity cost. Whenever you make a change to a product, you will impact everyone’s experience of it. And some of that impact will be negative.

Did Microsoft think their MS Word interface was going to look like this? No. But it does. And there are some super users who love that breadth of functionality.

But there are lots of users who just want a digital typewriter. And that’s why people like programs like Calmly Writer, where the entire toolbar is nine icons long.

Is this bad for consumers and businesses?

In short, no. It might be bad news for some companies, but overall it means that there are products that will suit novice users and products that suit more advanced ones. For example, for those engaged in the Airbnb ecosystem, can now book a place, find a restaurant, and plan their trip from within one app. On the other hand, new users can use VRBO, FlipKey, Homestay, HomeAway, Wimdu, Go With Oh, or any of the other competing apps. What’s more, there are exceptions.

Trello, for example, continues to provide a simple value proposition and a smooth onboarding process for new users, keeping their core offering fast and easy to use.

However, they’re also aggressively expanding their powerups options, where users can increase functionality to their heart’s content with almost endless integrations. They’ve also created a business product that again, increases functionality but, again, shields most new users from it.

Conversely, JIRA, a software project management tool, has gone in the opposite direction. It’s all about advanced users. It’s unapologetically difficult to get your head around. But by that same token, that’s why they’re a major contender in the software development space — their uncompromising complexity means that users have a lot of custom creation and control opportunities that advanced users seek out. And, because Atlassian went into JIRA with that complexity in mind, there is ample help documentation to bring new users up to speed.

Adobe has pursued the same direction for years with their Creative Cloud platform. Difficult to use for beginners? You bet. But the incredible feature density is why it’s the industry standard creative software.

Wrap-up: How apps can succeed (and avoid the slump)

The secret to producing an app that attracts users and keeps them coming isn’t new features. It’s about building a product that does one thing better than anything else. If that thing is editing editorial images to pixel perfect perfection, then yeah — it’s probably going to be complicated. Likewise, if you want your application to be the industry standard for shipping all kinds of software like Cisco, then again, it’s going to be a fairly feature-dense app.

Yes, user onboarding is going to suffer. But if you’re committed to doing a complicated task well, that might be a hit you’re willing to take.

Problems occur when features and functionalities are developed for the few and exclude the many. When business pressures and skewed user feedback work together to create new features that complicate matters but fail to work towards the primary purpose of the app.

For example, when Evernote highlights their Web Clipper instead of their checklist and organizational systems, or when Airbnb pushes their experiences instead of their homes, or when MS Word becomes so heavy, it’s difficult to use it to actually write.

When that happens, new entrants see their market opportunity and exploit it.

It’s possible to have your cake and eat it too — you just have to remember why you bothered to bake it in the first place.

You might be interested in our Popular Apss with Worst Reviews post or some tips and tricks on ASO Marketing.

“Highlighting my app’s best features is super easy using Placeit’s mockups”

Tim Roberts 5/5