How to Make the Most of In-App Purchasing

A successful in-app purchase (IAP) strategy is about finding the tipping point between enough functionality without IAPs to create a positive experience, but with enough added value once the IAP is made to justify the expenditure.

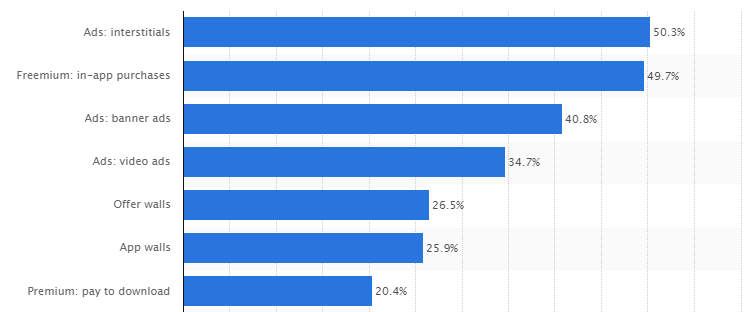

IAPs, either free or with a paid app, are dominating the app market, with almost half of apps in the App Store adopting the freemium IAP business model. Unfortunately, it’s not so easy to get people to use real money to buy digital things, like coins, points, a bonus item or unlockable content. So here are our thoughts on the art of IAP, and how you can use it to make yourself a little more moolah.

Quick note – before we continue, we need to be clear that most of the existing chatter about IAPs as well as most of their use in apps is in games, so that’s where I’m going to focus my attention.

Image via Statistica

The Rise of In-App Purchases

Before we get into the best way to use IAP (and, naturally, some examples) it’s important to recognize why they’re as popular as they are. And it’s not just that app buyers are cheap, although market expectations probably have something to do with it.

People like to try before they buy.

That’s it really. With the App Store T&Cs clearly stating:

It’s not entirely ridiculous that wary App Store peruse-ers would loathe to throw down $4.99 for something that might be total rubbish. Hence why the top two performing app store revenue modes are in-app ads and freemium IAPs – they barrier of entry for these is smaller (for a discussion of the economics behind this business model, have a look at Graham Spencer’s article for MacStories).

How do you make the most out of it?

It’s really all about perceived value. It’s not so much about that your upgrade version is going to make their app experience that much better, but more how people feel that it’s going to make their app experience better. Essentially, you want to give enough value that they’ll buy, but leave enough on the table that they’ll have a positive enough experience in the first place to feel that an upgrade would enhance the experience.

For example, imagine that SwiftKey was run on an IAP business model. You got 25 letters for free – but you had to pay for the ‘S’ key.

That would be a terrible IAP model! There’s not enough value derived from not using the letter ‘e’ to get the most out of the app to feel that you’d benefit enormously from further investment (as an aside, this sentence alone has 26 ‘e’s in it.). So their conversion would be terrible.

By comparison, really successful implementation of IAP is Letterpress. It’s a turn-based word game where you play against your friends. The free version has everything you’d want to function, but the IAP version lets you play more than two games at once.

So there’s enough functionality for people to experience the game and feel that it might be worth further investment, and it’s super clear exactly why they would want to pay more for it (to play more games at once).

Also worth mentioning is that Letterpress does a really good job of segmenting its audience into high value consumers, who are going to consume the IAP and low value consumers, who only want the free version. That is, they structured their IAP along the natural lines that these two groups are going to fall along. People who only play now and again at best, are probably never going to have more than two games on the go at a time. And that’s fine – they’re not exposed to the IAP at all. However, high-value consumers, who are super addicted and play all the time will want to play more than two games at once, and thus they get the IAP offer.

The IAPs targets the people they need to and avoid the people they don’t.

Essentially, a successful IAP strategy is about finding the tipping point between enough functionality without IAPs to create a positive experience, but with enough added value once the IAP is made to justify the expenditure. Obviously, this threshold is going to be different for every single app, so I looked at some common factors that might affect it below.

Finding the tipping point: common factors

So how do you find this magical place where as a developer you’re covered in riches (or, you know, above the $11,770 poverty line) and consumers are only too happy to part with their hard earned cash? It’s no mean feat, but here are some general guidelines that might be able to help you out.

Addiction level

In economic terms, what we’re talking about is demand elasticity. The less price affects demand, the more inelastic it is. Here’s an example. Price of kumquats is extremely elastic – it’s not often someone says ‘gee, I absolutely, 100% need that kumquat!’ compared to the price of crack cocaine, where lots of people say ‘gee, I really do need that crack cocaine.’

If someone is super addicted to a game or an app, either because it pushes all the right buttons, or because it’s an app that they use every day (like Spotify) then demand is going to be less elastic – that is, they’re going to pay for it no matter what the price.

Farmville 2, for a variety of reasons, has an amazingly inelastic demand due to their high addiction level.

If your game is highly addictive, then your hard core user base will be more willing to shell out for IAPs.

IAPs are tangible vs transient

People are more likely to spend real money on an IAP if they can look back and see tangible progress, rather than spending real currency for in-game currency, level power-ups or other game consumables. Garham Spencer from the previously cited article argues that this is because if you buy access to a new world or a new level, then you can track your progress; if you buy a consumable, then looking back down the line you having nothing to show for this.

Plants vs. Zombies 2 opted for both of these options, and in their Wired.uk review, they suffered for it. While they were praised for being free to try, the reviewer, Nate Lanxon argued that game required consumables to be purchased to beat certain levels, which led to the game having less to do with skill and more to do with financial investment.

Target users who want IAPs, but respect those who don’t

It seems like a really huge part of a successful IAP project is to make them accessible to those players or users who want them, but to retain enough core functionality for those who don’t. This is where Plants vs. Zombies 2 failed – it made it all about the IAPs, and as a result the free users suffered. Letterpress did a much better job of targeting users since their IAP offering was something only real enthusiasts would want.

iThoughts is another great IAP model. It’s a mind mapping tool, and it costs $11.99. Their IAP is essentially a beta version, so if you pay, then you get new features and functionality faster. It targets those users who want the most out of it (and use it a lot) without negatively impacting those users who are not as engaged.

Image via toketaWare

Wrap up

There’s no one way to know how to successfully execute an IAP business model. Lots of apps, like Punch Quest, have all the IAP functionality in place but fail to generate revenue. Others, like Plants vs. Zombies 2, might generate revenue, but at the cost of a positive gameplay experience. It seems like the best way is to focus on which users are going to buy and focus on what they want. Offer tangible things instead of consumables, so the gameplay isn’t bad for free users, but is expanded with IAPs. Focus on functionality that your addicted, every day willing-to-pay user wants but doesn’t adversely affect your on-the-subway, once in a while guy.

To me, a successful IAP strategy is about adding value to those who want it, rather than taking away value from the product and holding it at random with IAPs. There’s no one formula that’s going to maximize both developer profits and user experience every single time, but if the emphasis is on adding rather than taking it away, IAPs will be a lot better at getting close to the tipping point.